50 Ideas for Recruiting and Retaining Election Workers

Whether they’re staffing the polls, processing ballots, or fielding voter phone calls, your temporary election workers are invaluable. But many jurisdictions struggle to recruit enough, even without a global pandemic!

That’s why we’re rounding up your success stories. Elections aren’t one-size-fits-all, so steal ideas you like and ignore the rest. (If you missed the previous round-up, check out 39 Ways Election Offices are Responding to COVID-19).

We’d also like to highlight two additional resources: Power the Polls, a national poll worker recruitment effort, and our recent free webinar on Recruiting and Training Election Workers.

Categories:

Recruitment Pools

1. Voters. You already send mailings to voters, so why not recruit election workers at the same time? Wake County, North Carolina includes a buck slip in every voter mailing encouraging them to work the polls. Interested voters can return the buck slip by mail, email, fax, or apply online. The slips are inexpensive—only $0.025 each—and effective. Before, in 2010, Wake County received 345 poll worker applications. After introducing the buck slips in 2011, applications skyrocketed to 1,556! Additionally, you can recruit from your voter registration form, like Wyoming does.

2. Taxpayers. By partnering with neighboring government agencies, you can extend your reach to all taxpayers in your jurisdiction. Wake County partners with the revenue department to include the above buck slip in the annual tax revenue mailing. Fairfax County, Virginia has a similar partnership with their taxation department, which results in hundreds of election worker inquiries at less than 1¢ per buck slip. Another example is St. Louis County, Missouri, which includes this simple buck slip in tax bill mailings:

3. Community groups. Recruiting is easier when you tap into existing networks. Community groups range from veterans groups, to knitting clubs, to Rotary chapters. We highly recommend Orange County, Florida’s Adopt-a-Precinct model to leverage these networks (see idea #25). We also recommend targeting groups based on the skills and backgrounds your office needs. For example, recruit bilingual workers from cultural groups, tech-savvy workers from professional associations, civically-minded workers from service organizations, etc.

4. Bilingual populations. Whether you’re struggling to meet section 203 requirements or passionate about going above-and-beyond to serve your voters, bilingual election workers are the answer. When recruiting, be explicit about your language needs. San Mateo, California’s online job posting for a seasonal Election Materials Proofreader explicitly asks for Spanish or Chinese language skills. Harris County, Texas launched a #StepUpToServe campaign on social media emphasizing the need for Spanish, Chinese, and Vietnamese speakers. Chicago hired a liaison with the city’s Asian-Indian community organizations to recruit bilingual Hindi, Gujarati and Urdu speakers. And don’t overlook students! New York City partners with colleges and universities to recruit language interpreters. In 2016, 45% of Minneapolis high school poll workers were bilingual, compared to 13% of all workers. Tribal communities are another great source of bilingual election workers—Coconino County, Arizona staffs each voting location with at least two poll workers that speak the local tribal languages. It’s also a good idea to translate recruitment materials into the language you’re recruiting for, like Arizona does.

5. Underrepresented communities. Poll workers directly and indirectly influence how welcome voters feel. Madison, Wisconsin noticed that the vast majority of their election workers were white, even though Madison serves a diverse population. In order to diversify recruitment, Madison partnered with civil rights groups like the Urban League, the NAACP, and 100 Black Men. Instead of only recruiting through press releases, they advertised using Metro buses, public libraries, food pantries, job fairs, public housing, community dinners, neighborhood centers, churches, disability rights groups, universities, neighborhood associations, grocery stores, job centers, cultural media outlets, and more. Beyond poll workers, Madison also deputized 1,500 ambassadors to register voters in their communities and answer questions about elections.

6. Sign language interpreters. Many jurisdictions, like El Paso County, Colorado, hire ASL (American Sign Language) interpreters to work the polls. English and ASL are two different languages, so providing instructions in written English isn’t always effective for voters whose first language is ASL.

7. Disability groups. Many offices, like Washington D.C., recruit from local disability agencies and disability rights groups. It’s good to involve groups in the voting process who haven’t always felt welcome. As a bonus, people with disabilities are often more tech-savvy than your typical election worker. On California’s website, the Voters with Disabilities webpage provides both voter information and recruitment information.

8. Faith-based groups. Blue Earth County, Minnesota circulates election worker recruitment information in church bulletins. Faith-based groups are also fantastic candidates for the Adopt-a-Precinct program (see idea #25)—Orange County, Florida found that churches in particular are always looking for fundraisers and have been enthusiastic Adopt-a-Precinct partners.

9. High school students. Most jurisdictions recruit high school poll workers, and for good reason—they’re often tech-savvy and bilingual, and they’re more likely to become lifelong voters if exposed to the voting process early. The pandemic adds urgency to youth recruitment as well. In Chicago, thousands of youth staff every election thanks to a partnership with the non-profit Mikva Challenge and with history and social studies teachers. Ely, Minnesota also partners with a non-profit, Walking Civics, to recruit high school students and veterans to be trained together and serve together on Election Day. Montgomery County, Maryland has a comprehensive Future Vote program, which recruits students as young as 6th grade to help with election office work, voter outreach, operational support, polling place setup, etc. This creates a pipeline of engaged students who become poll workers when they turn 16 (over 10,000 and counting!). Minneapolis recruits from 33 high schools, and many have designated school coordinators that help with recruitment. Minneapolis found best results training high schoolers alongside regular poll workers, and paying the same amount, too. Minneapolis also found that different schools respond to different recruitment messages—some students want a college recommendation letter, others want community service hours, others want extra cash, etc. Uinta County, Wyoming awards extra credit to students who serve as poll workers. Additionally, high school sports teams and clubs are great Adopt-a-Precinct partners (see idea #25).

10. College students. Just like with high schoolers, it’s best to partner with the school instead of recruiting individual students. Colleges have built-in infrastructure for distributing information—orientation week, activity fairs, a campus listserv, info tables during lunch hours, job boards, student radio, etc. Northampton Community College set up recruitment tables with food, a magician, and a caricaturist, and 100 students were recruited in a single day. At California State University, Long Beach, cheerleaders attended events wearing “Love Me, I’m a Poll Worker” T-shirts, and anyone who filled out an application received a T-shirt too. College clubs, sports teams, sororities, and fraternities are great Adopt-a-Precinct partners (see idea #25). It’s even possible to bake recruitment into college classes. For example, Long Beach offers extra credit to students in introductory government classes, and this recruits over 200 poll workers each year. A professor at Suffolk University allowed students to serve as poll workers instead of writing a paper. A professor at the University of Iowa teaches a politics class with a service-learning requirement, and working the polls satisfies that requirement. Asnuntuck Community College designed an entire course around poll worker service with a curriculum on election history. However, college students have some downsides—residency requirements are challenging for out-of-state students, college students have a high attrition rate, and college recruitment programs take a lot of effort and coordination.

11. Teachers. Scott County, Iowa is reaching out to teachers’ groups and unions that may have workers idled by the pandemic. Miami County, Ohio has had luck recruiting retired teachers. They tend to retire early, they’re willing to serve their community, and they often recruit additional people. Miami County finds them by asking school districts for a list of retired teachers. Virginia reached out to the state’s college presidents and high school superintendents, asking them to recruit both teachers and students.

12. Political parties. In some states, like Illinois and Wisconsin, political parties are responsible for finding poll workers. Even if you’re not required to, it’s a good idea—especially if you need a bipartisan balance on your team. Political parties can tap into their network of civically-minded community members.

13. Government employees. A great source of election workers might be just down the hall in a neighboring government agency. Government employees tend to be civically-minded, professional, and already trained to interact with the public. You can also incentivize government employees by designating election work as paid leave or civic duty pay. This designation can happen statewide, like in California, or at the local level, like in Maricopa County, Arizona. In Florida, the state incentivized state-level employees, and encouraged each locality to do the same for local-level employees.

14. Local businesses. Franklin County, Ohio partners with local employers to recruit great poll workers. First, Franklin County conducts outreach to local employers. Then, they set up a display at the workplace, answer questions, and even let employees practice using voting machines. Successfully recruited employees are trained at their workplace to save them a trip across town. In some states, like Minnesota, employees are legally allowed time off to serve in an election without reduction in pay.

15. Stadium and sports employees. During the pandemic, we’re increasingly seeing large sports stadiums, arenas, and expo centers used as voting locations to minimize the risk of COVID-19 transmission. This option might come with an army of volunteer poll workers too! In Fulton County, Georgia, hundreds of State Farm Arena staff will be trained as poll workers. In Detroit, all Pistons employees get Election Day as paid time-off and are encouraged to work the polls. Already over 50 have volunteered.

16. Furloughed employees. There’s an unprecedented number of furloughed employees during the pandemic, many of whom have availability and would appreciate some extra cash. If election worker compensation doesn’t interfere with unemployment benefits, include that in your recruitment messaging! Nebraska, for example, clearly explains, “Poll worker pay will not reduce unemployment benefits for those who are unemployed.”

17. National Guard. Our fair, democratic elections are run by civilians, not by the military or the National Guard. So if your jurisdiction recruits from the National Guard, make sure they serve in a civilian capacity, in plainclothes, and in the jurisdiction where they vote—just like everyone else. Wisconsin leaned heavily on National Guard members to staff polling places, and Nebraska recruited them as standby poll workers just in case. Beyond working the polls, the National Guard assists over 30 states with election cybersecurity. In Colorado, for example, a team of 6 members help identify cybersecurity threats, vulnerabilities, and misinformation so Colorado can proactively address them.

18. Medical Reserve Corp. The Medical Reserve Corp is a nationwide volunteer organization that helps with disaster medical support, health screenings, public education, etc. In Virginia, they also worked at polling places! They worked as support staff, not regular poll workers—so they helped sanitize equipment, ensure correct usage of PPE, and maintain social distancing. If your nearby MRC can’t spare volunteers, you can follow Cape Girardeau, Missouri’s example and hire workers specifically to help with polling place sanitation.

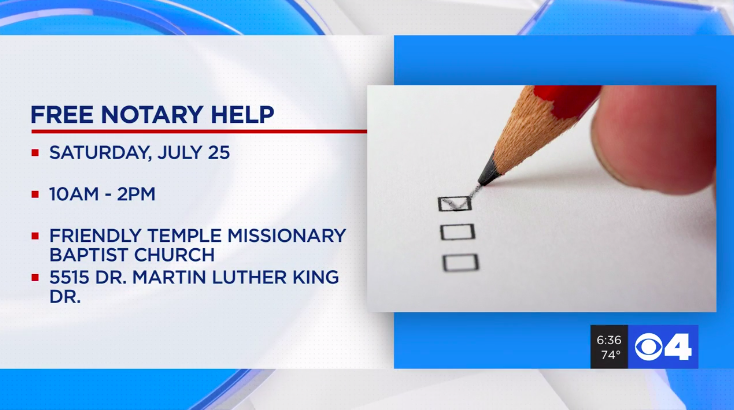

19. Lawyers. In Ohio, attorneys who receive training and serve as election workers receive CLE (continuing legal education) credits. Ohio had to overcome logistical challenges, like getting the Ohio Supreme Court’s approval, but the program’s been successful so far. Cuyahoga County, Ohio takes advantage of the professionalism and legal expertise by assigning attorneys to polling locations that haven’t performed as well. Nebraska liked this idea so much they copied and expanded it! You can also utilize lawyers’ skills more directly, especially if your mail-in ballot process involves notarization. In St. Louis, Missouri, the local bar association is providing free notary help as part of a “Promote the Vote” campaign.

20. Accountants. Nebraska expanded the above idea to include accountants. Nebraska partnered with the state Board of Public Accountancy and the Society of Certified Public Accountants Society to award continuing education credits to accountants who train and serve as election workers.

21. Realtors. Just like the above two examples, West Virginia partnered with the state’s Real Estate Commission to award continuing education credits to realtors who receive training and serve as poll workers. In Nebraska, the state REALTORS® Association is actively encouraging its members to serve as poll workers.

22. Librarians. It’s a natural recruitment pool—libraries often double as polling places and librarians love serving the public. In Chesapeake, Virginia, library staff have been helping prepare absentee ballot packets, sorting ballots, and answering phones. It’s especially possible during the pandemic, since many libraries are closed and librarians have extra availability.

23. Journalists. You probably don’t want to be overrun with journalists, but consider inviting one or two to serve as election workers. The behind-the-scenes perspective makes for compelling news, like this article on Rochester Hills, Michigan. After a detailed rundown of the ballot counting process, the article concludes, “It was a complete day, filled with boredom, laughter, fatigue, and some last-minute stress, and I’d happily do it again.” But be clear about the rules, especially rules around note-taking and recording.

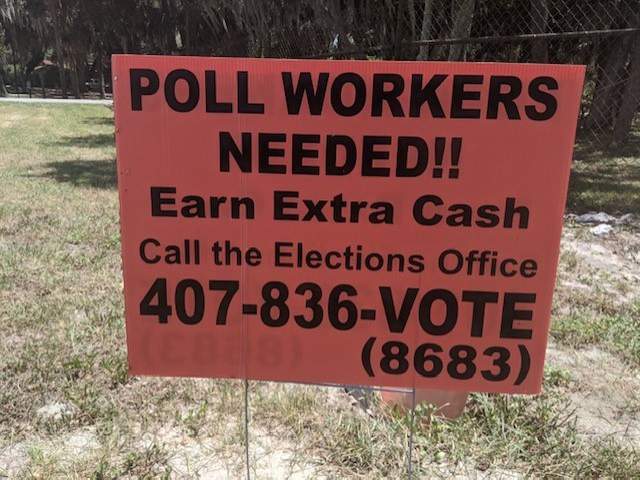

24. The general public. Of course, sometimes you recruit election workers without a target audience in mind. These general tactics include press releases, newspaper articles and ads, radio and TV public service announcements, flyers at the library, online job postings, etc. Orange County, Florida puts up signs in county parks, Nebraska launched an extensive print and radio ad campaign, and Madison, Wisconsin advertises on public transit. It’s important to cast a wide net.

Strategies and Policies

25. Adopt-a-Precinct. The popular Adopt-a-Precinct model dates back to the 1990s in jurisdictions like Orange County, Florida and Ventura County, California. Election Day is transformed into a fundraising and team building opportunity for community groups like churches, nonprofits, and fraternities. When a group “adopts a precinct,” they are responsible for finding enough volunteers from their organization to staff the polling place. Instead of paying each worker separately, the group receives a single check for working Election Day. Since the 90s, the program has spread to many Florida and California counties, as well as jurisdictions ranging from Wilson County, Tennessee to Blue Earth County, Minnesota and Wyandotte County, Kansas. States like Alaska and Nebraska rolled it out statewide. It’s often rebranded as “Adopt-a-Poll,” and even rebranded as “Adopt a Voting Site” in Milwaukee. And sometimes the rules are different—Kansas City restricts participation to verified 501(C)3 charities, whereas Alameda County, California welcomes any group, even families fundraising their own family vacation. Long story short—if you want to implement this in your office, don’t reinvent the wheel! Here’s some example materials:

- Organization signup form — Palm Beach County, Florida

- Breakdown of payments — Solano County, California

- Press release — Washoe County, Nevada

- Promotional brochure — Osceola County, Florida

- Promotional video — Alameda County, California

26. Focus on underserved areas. Madison, Wisconsin noticed an overlap between areas with fewer poll workers—“poll worker deserts”—and areas with low turnout. To address both problems, Madison targeted poll worker recruitment and voter outreach to these areas. Butler County, Ohio noticed clusters of precincts with high provisional ballot errors, so they focused recruitment efforts on those clusters and saw a decrease in provisional ballot errors.

27. Hire a professional recruiter. King County, Washington hired a professional recruiter to recruit temporary employees for data entry, ballot processing, and phone banking. Beforehand, these positions were filled on-the-fly, which meant last-minute hiring, worker shortages, and poor candidate screening. The professional recruiter helped King County hire a more skilled, professional workforce.

28. Expand the recruitment pool. Policy change takes time, effort, and sometimes advocacy, but it can pay off in the long run. West Virginia enacted a new law allowing poll workers to serve outside their home jurisdiction. California election officials advocated for a law allowing legal permanent residents to become poll workers so they could recruit more bilingual poll workers. In Nebraska, jurisdictions are legally allowed to “draft” poll workers, similar to jury duty. Maryland changed the age requirements so students as young as 14 can serve as Election Day pages, working two 4-hour shifts under the supervision of more experienced poll workers.

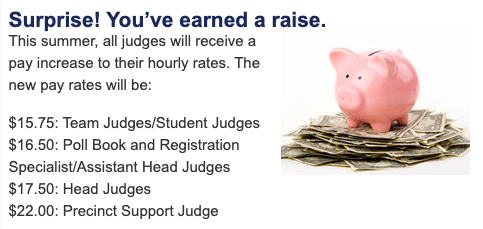

29. Increase pay. Election worker pay varies widely by geography, so there’s no one-size-fits-all amount, but generally speaking higher is better and many jurisdictions increase pay as a recruitment tactic. Additionally, some jurisdictions offer hazard pay during the pandemic, including several towns in Connecticut. You can also incentivize training—Guilford County, North Carolina pays workers an extra $35 per election if they complete a certification program. And it’s a good retention tool, like Minneapolis notifying previous workers that they’ve earned a raise.

30. Allow split shifts. Poll workers in particular face long, grueling days, often upwards of 10 hours. Understandably, this makes recruiting more difficult. To make the work easier, at least 18 states allow split shifts. These shorter, partial shifts can be far more appealing to potential recruits.

31. Run digital ads. Arizona is recruiting poll workers from a statewide Facebook ad campaign. Paid campaigns can increase your visibility and reach, and often let you target specific demographics (like county residents, a specific age range, etc.). But be careful—we heard a horror story from an election office that spent $5,000 on paid advertising, with no luck. If you’re new to ad campaigns, it’s best to do a trial run to determine what works in your community before investing a ton of money. If your budget is tight, prioritize “earned media,” which is free media coverage just by being interesting or newsworthy.

32. Make online sign-ups easy. Travis County, Texas partnered with the local League of Women Voters to create this simple online form, and responses go directly to Travis County officials. A statewide form is even better—like North Carolina’s. Maine created an entire website for election worker recruitment. When in doubt, if your current form is difficult, you can always promote Power the Polls, which makes national recruitment super easy.

33. Recruit extra workers. It’s easier said than done, but try to recruit more workers than you’ll need—especially with the pandemic’s higher attrition rates. Shasta County, California has 35-70 “standby” poll workers trained and ready to replace no-shows. Nebraska recruited 130 National Guard members as backup poll workers. Wake County, North Carolina assigns 300-500 poll workers to their “STAR” team (Support Trained and Ready). STAR workers aren’t assigned a polling place until shortly before Election Day, so they replace poll workers who change their minds.

34. Predict no-shows. If you like nerdy solutions, you’ll love Washington D.C.’s data-driven approach to predicting poll worker no-shows. First, they conducted a statistical analysis of previous records of attendance and absenteeism. The best predictor was previous poll worker service — for each previous election served, they were 3x more likely to show up. Additionally, older poll workers were more likely to show up (albeit before the pandemic). Using the data, D.C. assigned an absenteeism risk score to each precinct. They were better prepared to shift workers to at-risk precincts, and they cross-trained low-risk workers.

35. Partner with your state. Some strategies work better at the state level. The Nebraska Secretary of State’s office spearheaded several poll worker recruitment efforts, including mailing a poll worker application to every eligible voter aged 18-50 in the counties that requested help. And don’t forget your state association—in California, the Association of Election Officials helped achieve a policy change allowing legal permanent residents to serve as poll workers. Your state partners are especially useful when you need extra funding, a broader reach, or statewide coordination.

Effective Messaging

36. Celebrate election workers. North Carolina launched a Democracy Heroes campaign, which celebrates the heroes who step up to replace at-risk election workers. West Virginia launched “Operation Elective Service,” appealing to people’s patriotism during the pandemic crisis. Michigan launched a Democracy MVP campaign, which celebrates election workers as “the Most Valuable Players of our democracy, ensuring free and fair elections for all.”

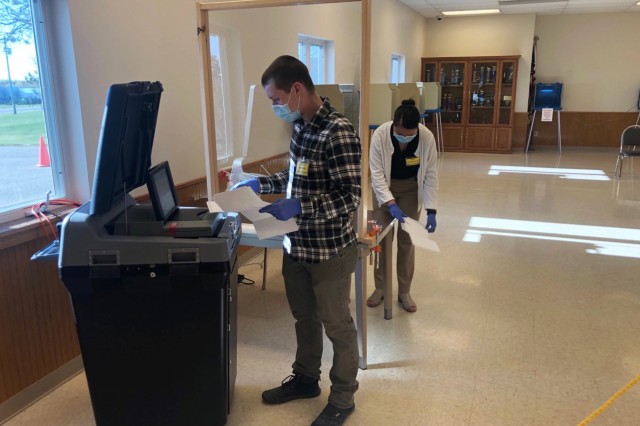

37. Emphasize safety measures. During the pandemic, many potential election workers are concerned about health risks. Sharing your safety plan can help them decide whether to serve. States like Arizona emphasize PPE, sanitation supplies, and social distancing protocols on the poll worker recruitment page.

38. Emphasize money. Recruits are often asked to “volunteer” for election work, leading the general public to assume election workers are unpaid. While election workers typically cite civic duty, patriotism, and community service as their main motivations, money sweetens the deal. And it’s eye-catching! Look at the poster below from Montgomery County, Maryland, used to recruit high schoolers, a population especially interested in some extra cash.

39. Explain your reasons. Sometimes you need to ask personal questions, like political party affiliation. Pere Marquette Charter Township, Michigan recommends explaining your reasons for asking—for example, you might be legally required to maintain a balance of political parties. Recruits feel more comfortable sharing sensitive information when they understand why you’re collecting it.

40. Create recruitment videos. Videos are an opportunity for creativity, showing the human side of elections, and getting noticed on social media. We love this Star Wars-themed video from Contra Costa County, California with nearly 1,000 views. Iowa’s recruitment video explains what poll workers do, which helps potential recruits know what to expect. Michigan created two professional-looking videos (here and here) to promote the Democracy MVP campaign. But you don’t need a huge budget—we also like this video from Rochester Hills, Michigan, which uses still images and text to get the message across.

Retaining Election Workers

41. Engage before the election. Recruiting election workers is useless if they don’t show up! Normally, in-person interactions before the election (like training sessions) help election workers feel invested. During the pandemic, with fewer in-person interactions, it’s important to engage your workers in other ways. Chicago is focusing on virtual communication leading up to Election Day, and is even considering making phone calls to each worker to help them feel prepared, engaged, and part of a community.

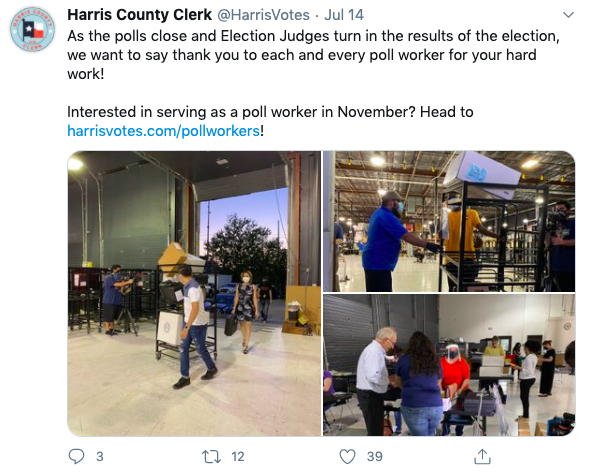

42. Thank your workers. It’s simple, obvious, and important. Thank your workers. Thank them collectively and publicly—on social media like Harris County, Texas, on your website like Larimer County, Colorado, in a video like Leon County, Florida, or in the newspaper like Cuyahoga County, Ohio. Thank them individually and privately—using email, text messages, or mailed thank-you notes. Experts on volunteer retention stress the importance of thanking your workers.

43. Invite feedback. If you want election workers to feel invested in your elections, involve them in the decision-making process. New Hanover County, North Carolina hosts a debrief meeting after each election to invite honest feedback, constructive criticism, and suggestions for improvement. Some election workers even participate in an ongoing focus group throughout the year. Similarly, San Francisco runs a poll worker advisory network that provides input on recruitment, training, materials, and processes.

44. Train them well. People like feeling prepared, and they don’t like feeling helpless. The quality of election worker training directly contributes to election worker retention. Guilford County, North Carolina offers an optional, above-and-beyond certification program for poll workers, and certified workers are more committed and more likely to return. They’re also more likely to serve as part-time election workers in the weeks leading up to their poll worker shifts.

45. Evaluate performance. You don’t want to retain all election workers—just the good ones! Montgomery County, Maryland created a Precinct Performance Report that recognizes high performance, identifies areas of improvement, and helps recruiters know which precincts need more attention. Allen County, Ohio recommends being transparent about the rubric you’re evaluating workers against so they understand expectations. You can also use performance evaluation to reward high-performers. In Humboldt County, California, if a poll worker team successfully completes its tasks and returns all the supplies and equipment correctly, every member of that team receives a $20 bonus.

46. Recognize consistent service. Every jurisdiction has veteran election workers that return year after year. Recognize and encourage this repeat service as much as possible! New Hanover County, North Carolina presents certificates and pins to poll workers who have served in 10, 15, and 20 elections. Orange County, California awards pins for poll worker service in 5-year increments. As a bonus, recognition ceremonies are great publicity—like Hamilton County, Ohio recognizing 59 years of poll worker service.

47. Provide election-specific pins. Voters love stickers, and election workers love pins! Jurisdictions like San Mateo, California provide election-specific pins featuring the year, the type of election, and a unique design. Other jurisdictions use a hanging design, like the picture on the right, where new pins chain to previous ones. No matter the style, these one-of-a-kind souvenirs become proud collections, encouraging workers to return and expand their collection. If you’re looking for inspiration, here’s a fun collection of designs.

48. Provide other swag. Tote bags, pens, notebooks, keyrings, t-shirts, water bottles, coffee mugs, etc.. If your budget allows, election worker swag is a great appreciation tactic. People are more likely to vote if it’s part of their identity—”I am a voter”—and the same logic applies to election workers. Sporting a Lyon County, Kansas Election Worker tote bag all year long reinforces that election worker identity.

49. Keep in touch via newsletter. Newsletters can keep your election workers engaged and returning. They can build camaraderie—Okaloosa County, Florida includes thank-you messages, photos, and even shares recipes. Newsletters can debrief previous elections—Contra Costa County, California shares stats like who processed the most voters and which high school supplied the most workers. Newsletters can even help prepare workers—both Monmouth County, New Jersey and Franklin County, Ohio explain Election Day processes and procedures in greater detail.

50. Profile your election workers. It’s a common practice to write short profiles on your election workers. Jurisdictions like Minneapolis include profiles in their newsletters. You can even use profiles as recruitment messaging, like Miami-Dade County, Florida does.

What else are you doing?

This list is long, but not exhaustive! What is your office doing? What have you seen other offices do? Email [email protected].